- Home

- Hannah Jewell

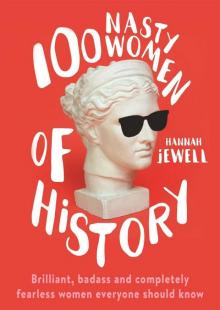

100 Nasty Women of History Page 8

100 Nasty Women of History Read online

Page 8

Her work was published in nine volumes between 1918 and 1924. Was her system called the Cannon method? The Annie J method? The Annie Can(non) Jump method? Nope, it was called the Harvard System. Which is, as Alanis Morissette would say, a little bit ironic, given that Annie was not made (or paid as) a member of the Harvard Faculty until she was in her 70s in 1938, just three years before she died.

For years, Annie hadn’t even been allowed to use a telescope alone, as it was seen as dangerous for a woman to do so. Which makes absolute sense. What if she saw something in the heavens that made her swoon or hurt herself or win a Nobel Prize? And, of course, a man and a woman using a telescope together, at night, when the stars were out, was an impossibly scandalous prospect. Women weren’t allowed to use the best telescope in the world, at the Palomar Observatory in southern California, until the 1960s. And no female astronomers – despite the fact that from the 19th century about a third of all those who worked in the field were women – would be elected to the National Academy of Sciences until 1978. (One Professor Johns Hopkins would vote against Annie’s election to the academy because … she was deaf. I can’t even understand the logic of this enough to make a joke about it. Just, what the fuck?)

As some fucking guy said to another female astronomer, Sarah Whiting, at the end of the 19th century: ‘If all the ladies should know so much about spectroscopes and cathode rays, who will attend to the buttons and the breakfasts?’ This guy, a senior European astronomer who considered himself very clever yet didn’t know how to make his own toast, sadly died shortly after making this statement by tripping over a box of buttons and landing face-first in a frying pan.12

The thing about Annie Cannon’s work, and the work of all the underpaid computers and astronomers in the Harvard Observatory and elsewhere, was that it was seen as a fundamentally female job. Even if women wanted to put forward their own theories, and do the fun, experimental bits of science, a huge amount of their time was taken up with rote labour and the collection and classification of data – which men would then use to publish papers under their own names, of course. Women like Annie were tasked with things like planning social events and fundraisers, and generally mothering everybody, much like things turn out in every office on the Planet Earth as we all hurtle together round and round our pleasant G2 sun.

A reporter for the Camden Daily Courier in 1931 wrote this when Annie Cannon won an important award for her work: ‘Housewives may be a little weak on astronomical physics. But they will understand just how Miss Cannon felt. Those heavens simply HAD to be tidied up.’ Shortly after publishing his report, that journalist sadly died by tripping over a large pile of laundry his wife had left untidied.13

Annie never had a family of her own, and lived, worked, and breathed the observatory. She was beloved by female and male astronomers alike – the men saw her as unthreatening to their greater man’s work. She was indeed a motherly figure, and received many awards in her lifetime for her classification work. She was the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, which, if you haven’t heard of it, is a university that people go to in order to learn how to become insufferable for the rest of their lives.

While Annie broke down barriers and supported other women in science for her entire life, in addition to her work toward women’s suffrage in the US, she was still quite a traditional person who believed that yes, certain types of science were more suited to women than others.

But other women in the lab were more radical than her, fighting against their poor working conditions. Williamina Fleming, who had taught Annie Cannon, pushed back against the fact that she was paid a thousand dollars less than her male counterparts yearly – a lot of money in those days. And, hell, a lot of money now. Fleming wrote that Pickering ‘seems to think that no work is too much or too hard for me no matter what the responsibility or how long the hours. But let me raise the question of salary and I am immediately told that I receive an excellent salary as women’s salaries stand.’ Beware bosses who say you should simply be grateful to be there.

Another woman working in the observatory, Antonia Maury, wanted recognition for her work. She wanted credit, and she did eventually manage to scrape some for herself. And another, Henrietta Leavitt, worked herself to death for Pickering, who published the results of her work under his name in 1912. Leavitt’s observation of something called the period-luminosity relationship meant that for the first time ever, scientists could work out the distance of stars, and indeed, the size of the entire universe.

But none would fight harder, or achieve more, than Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, the subject of the next chapter, who said that Pickering’s employment of Leavitt to ‘work, not think’ would ‘set back the study of variable stars for several decades’. Now let’s hear more about Cecilia.

30

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin

1900–1979

You’ll already be familiar with the conditions under which Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin carried out her work as a female astronomer at the Harvard Observatory, because you’ve just read the last chapter. I know you have just read the last chapter, because you’re not the kind of person who sits on the toilet and randomly turns to any page where your curiosity might lead you, like a monster.

Because you are not reading this carelessly on the toilet, but in a handsome leather armchair beside a roaring fire, you will remember quite clearly from the previous pages that Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was one of the many women who worked in the Harvard Observatory in the early 1900s.

Cecilia kicked off her academic career in brilliant style, proposing in her PhD thesis – which is still today considered one of the most brilliant astronomy PhD theses of all time – that the stars were not made up of the same elements as Earth or other planets, but rather were mostly hydrogen, with just a splash of helium. She showed this by building on the work of an Indian scientist named Meghnad Saha to prove that the different spectra classified in earlier years by Annie Jump Cannon & Co. were actually related to the relative temperatures of stars, that is, how smokin’ hot they were.

Now, science isn’t about being right all the time. Before you can advance the great spectrum of human knowledge, you’re probably going to be wrong a lot of the time. And yet, friends, here we have a young Cecilia being exactly spot on right out of the gates. Her thesis wasn’t just the best, but was actually the first astronomy PhD at Harvard by anyone – she hadn’t been allowed to get a PhD in Physics, and so cobbled together a committee to create an astronomy PhD programme for herself instead. And, well, technically she received it from Radcliffe College, the bit of Harvard that could give PhDs to women, because Harvard itself certainly wouldn’t. Harvard has since gotten over itself, in this regard at least.

Speaking of the committee, Cecilia received pushback from two supervisors, Arthur Eddington and Henry Norris Russell, who read her idea that stars were made of mostly hydrogen and just weren’t having it. They encouraged her to play down this aspect of her thesis, and she did. Russell would, however, a few years later come to the same conclusion on his own, and decide she was right after all. He, being a man, got to share the credit for the discovery, but Cecilia did shoot to international fame. She was the youngest astronomer to ever be featured in a publication called American Men of Science, which was ironic, because she was actually originally English.

After getting her PhD, Cecilia started lecturing at Harvard – but her classes would not be listed in the course catalogue for a full 20 years. The president of the university, A.L. Lowell, a man with many buildings and streets and libraries named after him, told her he would never in his lifetime give a faculty position to a woman. Sadly, after making this statement, he died by being crushed by a course catalogue falling from a great height.14 Cecilia wouldn’t become a full professor until 1958, when she was in her 50s – the first woman to be tenured from within Harvard. In the meantime, she was paid terribly, and struggled to make ends meet for most of her career, having to pawn her

jewellery to get by.

While Pickering headed up the observatory in Annie Jump Cannon’s day, Cecilia worked under Harlow Shapley. This was a man who she once shocked by giving a talk at Brown University while pregnant, which is fair enough, because everyone knows that pregnant women are rendered incapable of speech.

Cecilia had actually been denied a full professorship years earlier, in 1944, due to her ‘domestic situation’. It was one thing to be a matronly woman without children like Annie Jump Cannon – it was another to try and be a wife and a mother and to carry on in her work. She managed to raise three children while maintaining her career – which was not the done thing in the day. She’d bring her kids to the observatory, where they would run around pissing people off while she worked. In her limited free time, Cecilia’s hobbies included chain-smoking and punning in different languages.

Struggling under financial hardship, and being burdened with much of the social and busy work of observatory life because she was a woman, Cecilia nevertheless carved out a reputation for herself as a scientist of the highest order, and became the chair of her department.

The next time you look at the night sky, make sure to remind whoever is attempting to share a romantic moment with you that so much of what we know about the stars is down to a room full of underpaid and underappreciated women scientists. If they are not put off by this fact, you may kiss them.

31

Hedy Lamarr

1914–2000

Girls can either be pretty, or they can be smart. Any overlap between the two traits would be far too confusing for society to accept. If a woman is both, how are you supposed to know whether to get a boner or just to get angry? Being beautiful as well as intelligent has therefore been rightfully banned. Hedy Lamarr, though, was a brazen rule-breaker who was both a glamorous movie star and an inventor, the dangerous harlot!

Hedy was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in 1914 in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. In the 1930s she was a stage actress in Vienna who came to be known as ‘the most beautiful girl in the world’, a title now held by my friend Gena. She starred in her first film in 1931, Ecstasy, which was as scandalous as its sounds, featuring naked running, naked swimming, and simulated sex. It was banned in Germany, not because it was too scandalous, but because its cast and crew included many Jewish people, including Hedy, though she was brought up Catholic. Even the Pope condemned the film for depicting a simulated female orgasm, which as we all know is an invention of the Devil.

Hedy’s first marriage was to an abusive bastard, a wealthy weapons-mogul who sold arms to all the biggest bastards of the day. He loved fascism, for Europe as well as in his home, and cut off Hedy’s finances and controlled her every move. She later described herself at 19 as living ‘in a prison of gold’. When Hedy’s scandalous film was submitted to US censors for a possible release there, he bought and burned all copies of the film he could get his hands on.

Hedy knew she had to escape if she wanted to survive and continue her acting career. ‘I was like a doll,’ she said. ‘I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded – and imprisoned – having no mind, no life of its own.’ She made her escape, she said later, by disguising herself as a maid and fleeing to Paris, where her husband tried and failed to pursue her. She then went to London and managed to arrange a meeting with the president of MGM, Louis B. Mayer. He thought her work far too risqué for an American audience, though, telling her she would ‘never get away with that stuff in Hollywood’ and that ‘a woman’s ass is for her husband’. (Actually, Louis, a woman’s ass is for sitting, pooping, shaking to Shakira songs, and marching women to courtrooms to divorce their rich husbands and milk them for all they’re worth.) He did offer an entry-level contract for MGM if she paid her own route to get to Hollywood, but Hedy wanted much, much more for herself. So she snuck onto his ship, pretending to be the governess of a boy on board, to continue their negotiations on the way to America. By the time they arrived in the United States, she had a contract to be one of MGM’s new stars, and the stage name Hedy Lamarr.

Hedy’s breakout role was in the film Algiers in 1938, in which she played a mysterious hot woman, who didn’t speak much, as Hedy was still working on her English and playing down her Austrian accent. The film was a huge hit, and Hedy a new star, as women sought to imitate her black wavy hair parted down the middle and her sensible skirt suits.

But Hedy didn’t put much stock in her celebrity as a beautiful woman. ‘Any girl can be glamorous,’ she said. ‘All she has to do is to stand still and look stupid.’ They don’t give you that advice in women’s mags, do they? Hedy was also not one to go out and party with the Hollywood elite. Instead, she preferred to stay home and sketch out inventions at a drafting table.

Her most important invention was something called frequency-hopping. She had recalled from her days married to her first bastard weapons-mogul husband that a problem of torpedoes was that their radio guidance could be jammed and hijacked by enemies. And so Hedy and her friend George Anthiel developed frequency-hopping, a technology vital to wireless communications, which prevented this problem. The pair were granted a patent in 1942, but it would be a few more decades before the US military would begin to make use of it.

Today, this frequency-hopping technology is the basis of Wi-Fi and mobile phones, things that nowadays people literally die if they are left without for more than a couple of hours. Who knows how many teenagers have been saved by Hedy’s invention?

Because Hollywood values its boners more than its people, as Hedy began to age, the roles began to dry up. In WWII, Hedy wanted to move to DC and join the Inventor’s Council to help the war effort with her inventing skills, but she was told she’d be of more use as a movie star touring the country selling war bonds. She raised $25 million this way, and also worked entertaining soldiers. During the war, at the Hollywood Canteen, a club which saw off soldiers about to go overseas, Fridays were Hedy’s night. She would try to dance with every single one of the thousands of soldiers who gained free entry with their uniforms.

She spent her later years enjoying those classic old people pastimes of shoplifting, suing people, and moving to Florida. In her life, she married and divorced six men. She was never one to stick around if something wasn’t working. Once, unbothered about attending her own divorce hearing, Hedy sent her old Hollywood stand-in in her place.

Before she died in 2000, Hedy finally gained recognition for the many technologies spawned from her frequency-hopping patent, as well as residuals. Girls: make sure you get paid what you’re worth, no matter who you have to sue. It’s what Hedy would have wanted.

32

Louisa Atkinson

1834–1872

Caroline Louisa Atkinson, known as Louisa to her buddies, was born in 1834 in New South Wales, Australia, and from a young age became interested in botany and zoology. Australia is a very good place for a person to be interested in the natural world, as it is famous for its ten-foot-tall spiders, talking kangaroos, insatiably horny rabbits, and murderous, rabid koala bears known to drop from trees and kill unsuspecting passers-by. Or at least this is what I have been led to believe about Australia.

Louisa was a frail child, as 100% of 19th-century children were, but enjoyed learning all she could from her mother Charlotte, a former teacher who home-schooled her. When Louisa’s father died, she and her mother moved to Kurrajong Heights, west of Sydney, to live with her mother’s new boo. There, she loved to explore the forests around her new home. She began writing articles and sketching the plants (and talking kangaroos) she saw on her excursions. Louisa sent specimens to the various rock star botanists of the day, and in this way got to put her name on a few new species she’d identified, such as the Erechtites atkinsoniae and Epacris calvertiana (for her married name, Calvert), which everybody knows and loves today, and are probably plants of some kind, or possibly varieties of talking kangaroos.

Louisa gained fame for her natural history and botany publications and her plan

t discoveries, but she also wrote popular novels and fictional serials for Sydney newspapers in the 1860s and 70s, because it’s always good to have a side-hustle. Like so many aspiring scientists and adventurers of the 19th century though, Louisa created a stir by trading her unwieldy skirts for trousers, much more practical for trudging through forests. She was judged for this, by people who we can confidently assume never did anything interesting in their entire lives. You can find their biographies in my next work, People Who Never Did Anything Interesting In Their Entire Lives, coming soon to a bookshop near you.

33

Laura Redden Searing

1839–1923

Laura Redden Searing was a journalist who reported on the US Civil War – that’s right, lady journalists go way back, and not just covering fashion and cooking, despite what modern male editors may believe women are most suited to. In addition to her journalism career, Laura was also a poet, was deaf, and had the strange and awkward honour of being friends with both Abraham Lincoln and his future assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and also Ulysses S. Grant, because apparently there were only about five people who lived in Washington DC in the 1860s. I guess if you were friends with two people and then one shot the other, you’d quietly unfriend the murderer on Facebook and not bring it up at the funeral.

Laura graduated from secondary school at the Missouri School for the Deaf in 1858, and performed her poem ‘A Farewell’ in sign language at the ceremony. This was a time when there were debates about the education of deaf people, with some believing that teaching sign language rather than speech would prevent the mastery of English language and even of abstract thought. Laura’s ability to write in rhyme and also speak poetry in sign language proved these assumptions about deaf people wrong.

100 Nasty Women of History

100 Nasty Women of History