- Home

- Hannah Jewell

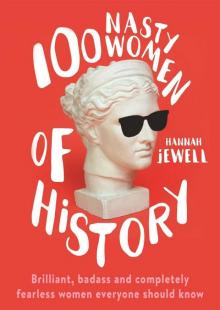

100 Nasty Women of History Page 7

100 Nasty Women of History Read online

Page 7

But Kartini’s greatest passion was education, and her dream of dreams – a school for native Javanese girls that did not discriminate according to class – would not die with her. In the years after her death, such schools were founded and named for her: Kartini Schools. In 1901, Kartini wrote to Stella about her great desire that such schools would someday exist: ‘What an ideal institution that boarding school for native young ladies would be: the arts, academic subjects, cooking, domestic economy, needlework, hygiene and vocational training will and must be there. Dream on, dream on, if it makes one happy, why not?’

26

Emmy Noether

1882–1935

If you can name a prominent woman in the history of mathematics, it’s probably Ada Lovelace. So this chapter is not about Ada Lovelace. Shout-out to Ada, you mad queen of algorithms, may your memory live on, except for right now.

No, this chapter is for another woman mathematician, a certified genius whose work contributed to the understanding of the entire universe, who you may never have heard of, because History Is Bad. Her name was Emmy Noether.

Emmy Noether was born in 1882 in Bavaria to a mathematician father. She wasn’t a spectacular student, but she once solved a complicated logic problem at a children’s party. Because apparently setting complicated logic problems for children was the done thing at kids’ parties in 1890s Bavaria.

Emmy qualified as an instructor in English and French, but decided she wanted to go to university to study maths instead. It’s what her dad did, so why not her? And it all worked out perfectly well! She was accepted into the university as an equal to her male peers, and went on to enjoy a successful and richly rewarded career as an academic.

Ha ha, just kidding. It wasn’t that easy, because, SURPRISE, men are bad, and she wasn’t allowed to properly enrol in the University of Erlangen. This was on account of her having lady bits. According to the opinion of the day, only people with willies could do maths, because willy-having and mathematical ability were directly related. Strangely enough, some very lonely people still believe this today.

Told she couldn’t enrol as a proper student, Emmy could only audit classes with special permission granted by each professor. So that sucked. Eventually Emmy took an examination to let her officially pursue a doctorate, and destroyed it with her big, mathsy brain. At this point the university was like, ‘Fine’. She went on to get a PhD writing a dissertation which she later actually described as ‘total crap’.

Crap or not, she stayed at Erlangen to teach for the next seven years, for which she was well respected and even better paid.

Ha ha, just kidding. Gotcha again! You forgot that the world is bad and always has been. The university let her teach, but only on the small condition that she wouldn’t be paid. At all. For seven years. Yes, a century before Lean In, there was the much less inspiring Teach for Seven Years Without a Salary for Love of Your Work and Out of Gratitude for Being Allowed To Work At All.

The mathematician David Hilbert then invited her to come and work with him at the University of Gottingen, but, SURPRISE, the university wasn’t having it, on account of her having a big ol’ vagina. While the lovely nerds over in the mathematics department were happy for her to join them, knowing her to be just as mathsy as they were, the other departments were firmly opposed to the idea of a woman faculty member.

One professor, whose name literally doesn’t matter, apparently asked Hilbert, ‘What will our soldiers think, when they return to the university and find that they are required to learn at the feet of a woman?’

Oh yes, professor. What a very good point that is. What could be worse than returning from the hell of trench warfare to find that your maths professor has BREASTS? What could be worse than surviving the unimaginable horrors of the First World War only to have to lie down at the feet of a lady person to learn! (Also, didn’t these people have desks?)

Hilbert replied to the professor that Gottingen was a university, not a bathhouse, so it really shouldn’t make a difference if Emmy were a man or a woman.

Again, the university was like, ‘Fine’, and let her teach. Kind of. She had to teach her courses listed under Hilbert’s name, to create the appearance of it being a man’s lecture.

And she still would not be paid a salary. Is that not the most being-a-woman thing you’ve ever heard?

Emmy was at least privileged enough to carry on in this way, with slightly mysterious sources of funding, and so she did. She also kept up her jovial nature in the face of the ridiculous hoops she had to jump through in order to do the thing she was good at. It’s a skill shared by so many of the women in these pages: the ability to leap through great flaming hoops of bullshit while keeping a smile on their faces.

At Gottingen, Emmy would take long walks with her students to talk about mathematics and develop an all-encompassing theory of the universe while also getting a bit of invigorating exercise. (I apologise to any reader who happens to be lazily lying in bed while reading that sentence.) Her students came to be known as ‘Noether’s Boys’ – which would incidentally be a great name for a punk band.

In 1918, Emmy published Noether’s theorem. What is Noether’s theorem? I don’t know, I’m not Emmy Noether, am I? Thankfully, though, I have made my pal Kelly, the queen of science, explain: ‘It’s the idea that if an object obeys a certain law of symmetry it will also follow a corresponding law of conservation. For example, if a process happens in the same way regardless of when you do it, so it has a sort of symmetry in time, you know energy will be conserved, meaning it can’t be created or destroyed, within that process too.’

Emmy’s work proved foundational to theoretical physics, supplemented Einstein’s theory of relativity, and also, on the side, she invented something terrifying called ‘abstract algebra’.

So after publishing one of the greatest mathematical theories of all time, and with the support of woke baes Hilbert and Albert Actual Einstein arguing on her behalf, the university was finally like, ‘Fine’, and in 1919 allowed Emmy to lecture under her own name at last. Finally, in 1922, the university granted her a small salary for the first time, as well as a title approximately equivalent to ‘Associate Professor Without Tenure’. They may as well have given her the title, ‘Eeeeew, A Girl Professor! Gross! Don’t Let Her Touch You Or You’ll Get Girl Germs!’

Luckily, Emmy Noether really loved maths, and focused on her work instead of the cascade of bullshittery being constantly flung at her by the world.

But imagine what she could have done if men were less terrible, you know? Imagine having to try and convince men that having lady bits instead of a willy has nothing to do with mathematical ability? Imagine watching your less-spectacular male colleagues surpass you in position and pay at the university, when all you really want to be doing is uncovering the mathematical mysteries of the universe in peace?

That’s a lot of wasted energy.

Then again, Noether knew a lot about the fact that energy can be neither created nor destroyed. I’m sure there’s a great metaphor in there somewhere – please consult your local theoretical physicist, or my pal Kelly, to explain it properly.

Emmy’s story ends, as too many have, with the fucking Nazis. Actual old-timey Nazis, not Twitter Nazis, or virgin-basement Nazis, or jizz-stained sweatpant-wearing Nazis, or senior adviser to the President of the United States Nazis.

Nope, these were actual 1930s Nazis, who dismissed all women and Jews from academic jobs – so that was Emmy doubly out, as a Jewish woman. Used to working without pay, she carried on doing some teaching in secret. Once, a student turned up in a Nazi uniform. She carried on teaching, and apparently laughed about it later. Because, well, how ridiculous of him, to be a Nazi.

Emmy then moved to the US in 1933, taking up a position at Bryn Mawr where she resumed her mathematical walks with a group of ‘Noether Girls’ – which would incidentally *also* be a great name for a punk band.

She died only two years later in 1935 after compli

cations from surgery for an ovarian cyst. So, Nazis and poor women’s health care took her in the end. In a letter to The New York Times shortly after her death, Einstein called her a genius, and the best-yet example of what could become of the education of women.

How many more Emmy Noethers could there have been in the world? How many with the ability to shape the course of human knowledge, but who couldn’t afford to work for free – or were stopped before they even began, by people who fervently believed that having a willy counted for anything? You’d need a great mathematician to work out the number.

27

Nana Asma’u

1793–1864

Nana Asma’u was born in 1793, one of the many children of Usman dan Fodio, the founder of the Sokoto Caliphate in what is now northern Nigeria. He was a great proponent of the education of women in Islam, and Nana benefitted from the tutelage of her father, her siblings, and her stepmother. She spoke four languages perfectly and was one of those prodigy children everybody dreads hearing about in other people’s Christmas round robins.

By age 14, Nana was a teacher herself, first lecturing the women and children in her own household, and then expanding her educational ambitions to the women of surrounding villages. Nana was such a keen bean, in fact, that she set up an entire network of women educators who fanned out into remote and rural corners of Sokoto to lecture and teach. Children, young women, and women in middle age benefitted from Nana’s organisational zeal, and a system which enabled women to take lessons while still looking after their families and their homes.

As anyone who has one in their family will know, teachers always get a ton of presents, and women sent honey, grain, butter, cloth, and other such gifts to Nana, the head teacher of the whole region. Since she was, well, rich, and also a keen bean, as we have discussed, she donated these goods to the disabled, sick, and needy. Yes, she would be a terrible person to have known on Facebook in moments of low self-esteem.

Nana didn’t spend all her energy on educational reform, however. She also liked to kick back, relax, and write intensely complex poetry in one of the languages in which she was fluent. Nana adapted classical Arabic poetic forms to the languages of Sokoto like Hausa and Fula, and as she got older was so respected for her fine, ridiculous mind that she was called upon to advise emirs and caliphs.

Today, she is still remembered in Nigeria for being a keen bean, a woman who probably everybody should try to be more like, and an early example of someone who lobbied for the rights and education of women. Basically, she was a 10/10 good egg, and while she faced some conservative haters who disagreed with the idea that women should be educated at all, she was incredibly good at explaining to them, in four languages, why they were actually idiots. This is a skill we must all practise and develop.

28

Jean Macnamara

1899–1968

In order to be a good sexist, you need to be able to do some impressive mental gymnastics to find reasons why women cannot and should not do things. One great example of this in history was the excuse used for years as to why women couldn’t be doctors in Melbourne at the start of the 20th century. Was it that they might swoon at the sight of blood? Was it that their periods would get all over the hospital floors and make everything horribly slippy? No, the reason given to Jean Macnamara in 1923 at Melbourne’s Royal Children’s Hospital as to why they couldn’t possibly employ her, a woman, was this: ‘Soz, babe, there aren’t any girls’ toilets.’ Well, not in that language exactly. Or, maybe in that language exactly – after all, we are talking about idiots.

Anyway, they did end up letting her work there, and it’s a good thing too, because she only went ahead and helped cure polio. She also must have figured out how to hold her wee for a full working day.

A polio epidemic in 1925 led to Jean’s research which discovered that there was more than one strain of the polio virus. It was a vital step toward the eventual vaccination created by Jonas Salk in 1955, thanks to which you and I in 2017 don’t even have to know what polio is. Some of Jean’s other theories about the treatment of polio would later be questioned, but if you would like to criticise her for that, please revolutionise some aspect of medical science and then go right ahead.

Jean was born in 1899 in Beechworth, Victoria, and was witty and blunt, both in her manner and in being five feet tall. She worked non-stop and was so trusted as a doctor – especially by children – that families would wait as long as it took to be seen by her. Her specialism in orthopaedics led her to devise new ways to splint different parts of the body, and she advocated new methods for the care of disabled people, particularly children. She was invited to the White House to meet President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had been paralysed by polio himself.

The other bit of Jean Macnamara’s legacy is kind of grim if you’re into rabbits. See, in the 1880s, some English hunter types introduced rabbits to Australia, which would have been fine if they’d shot them then and there. But nope, those rabbits got loose and did what rabbits do best – rabbit fuckin’ – and by 1950 there were a full-on billion rabbits wreaking havoc on Australian agriculture, doing all kinds of bad rabbit shit like eating sheep food and pooping everywhere and rabbiting around getting up to all kinds of naughty, rabbity japes.

Jean encouraged the government to make use of the rabbit-murdering myxoma virus to reduce the population. When at first it didn’t work, she pushed them not to give up on the experimental method. When myxomatosis at last began to be spread by mosquitos and to truly go viral, as the kids say, she was proven right. The rabbit population was fucked up, and the headline of the Lyndhurst Shire Chronicle in 1952 read:

GRAZIERS THANK WOMAN SCIENTIST

The sheep farmers – who had been saved about £30 million thanks to the end of the rabbit menace – gave her an £800 wool coat and a nice clock as a thank you.

Next time you are menaced by a rabbit, or feel grateful to have not died in childhood of polio, don’t forget to remember Jean, and, like the graziers,

THANK WOMAN SCIENTIST

29

Annie Jump Cannon

1863–1941

While researching the life and work of the astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, I quickly realised that I couldn’t properly tell the story of the women astronomers at the Harvard Observatory at the turn of the 20th century without also talking about Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, who followed in Annie’s footsteps and went above and beyond in her scientific achievements. So, lucky you, we will be hanging out with the ladies of Observatory Hill in Cambridge, Massachusetts, for two whole chapters.

If I know anything about space, and I don’t, it’s that there’s quite a lot of it. If you asked me how many stars there were in the universe, I would say, ‘loads’. If you asked me to categorise all the stars in the night sky, I would say, ‘No thank you, I would rather spend the time in bed watching The Bachelorette.’

When Annie Jump Cannon came to work at the Harvard Observatory in 1894, however, The Bachelorette didn’t exist yet, so instead she spent her time inventing a stellar classification system which was SO stellar that it’s still used today – and used it to record and catalogue 400,000 stars. Which, if you’re unfamiliar with the subject, is loads of stars.

Annie had been interested in the stars since her childhood in Delaware, where she and her mother would observe the night sky from their DIY observatory in the attic. Her supportive parents sent her to study physics at Wellesley, a women’s liberal arts college, after which she spent a decade wandering about and dabbling in photography and music, as 20-somethings of any era are prone to doing.

When she joined Edward Pickering’s team at Harvard11, she was just one of many women he employed as computers in the Observatory. In those days, a computer was a person, rather than something you use to watch The Bachelorette in bed. Pickering employed women because you didn’t have to pay them as much as men, a ridiculous idea that has thankfully died out with the passage of time and has never affected me personally, or any

women I have ever known. Together, the women were known at the time quite creepily as ‘Pickering’s Harem’.

So what was Cannon’s and the other women’s task, for which they were paid little more than unskilled labourers, and a whole lot less than a male scientist? At the turn of the century, there were about 20 different systems proposed for the classification of stars, and no one could work out the best way to do it. Annie came up with a system of letters and numbers by looking at their spectra – basically, if you put a certain star’s light through a prism, what kind of rainbow would you see? The pictures of the spectra for each star were not however nice Instagram photos of rainbows, but rather, glass plates with smudges and dots and blurry bits.

Annie, who was deaf for her entire career and relied on lip-reading, would remove her hearing aids while she worked in order to have absolute focus. She could read out what kind of star each of the spectra indicated by merely glancing at the plates. ‘She did not think about the spectra as she classified them,’ one of her colleagues explained. ‘She simply recognised them.’ She did this for more than 200,000 stars visible from Earth down to the ninth magnitude, which are incredibly dim (no offence to ninth-magnitude stars). Later, she expanded the work to go all the way to the 11th magnitude, which are the most idiot stars of all. Our sun, the most popular star among Earthlings, is a G2. This means it’s one of the second hottest types of yellow stars. (But don’t worry, Sun, you have a way better personality than the first-hottest stars.)

100 Nasty Women of History

100 Nasty Women of History